Like a lot of drivers, Martin Dover loves what he does — and has ever since the first time he climbed into the cab of a truck. Like a lot of drivers, he’s experienced the joys of the open road and the perils of being apart from his family, which are part and parcel of the career he’s chosen.

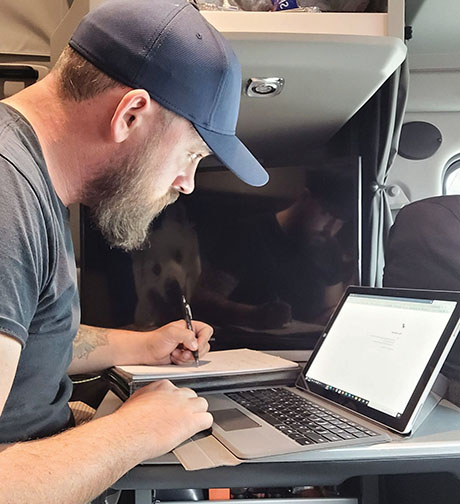

But unlike a lot of drivers, who after a long day want only to get some grub and shuteye, Dover shifts into a new gear when he puts his rig in park for the night. The 32-year-old fires up his computer, logs on and tends to the day’s schoolwork, moving him one step closer to his dream of earning a bachelor’s degree in logistics and transportation.

“You have options as to how many classes you’re willing to take,” he said. “I’m currently taking two classes per quarter, and that’s considered full-time. Each class is eight weeks long. I have to read about what topic we’re discussing and then post in a discussion forum by either Wednesday or Thursday (of each week), depending on the class. Then, by Sunday, I have to do a quiz or write a paper.”

He shrugs. “The workload isn’t too heavy,” he said.

Granted, compared to the physical demands and inherent hazards of over-the-road trucking, reading a couple of chapters or knocking out a quiz feels like small potatoes. Nonetheless, Dover‘s motivation to see his degree through is admirable. At five years and counting, the road to earning a college degree is the longest haul this driver has been on, outdistancing runs to 48 states and Canada.

“I currently have 79 out of 120 needed credits. My personal goal is to be done with it by the first of 2022,” he said. “I had to take a break after two years because I was involved in an accident and everything got destroyed. I actually rolled my semi.”

Another shrug. “No harm, no foul,” he said.

As a population category, truck drivers have lower than average educational attainment compared to workers in other professions, per the U.S. Census Bureau. Only 7% of truck drivers hold a bachelor’s degree compared to 35% of workers overall, even as the industry has reached an all-time high in number of drivers (3.5 million). That growth is driven by younger adults who typically have more education.

These facts aren’t lost on Dover, who said he doesn’t see many of his peers sharing in his goal of earning a college degree.

“For your Average Joe driver, I don’t think it’s something that they might be interested in,” he said. “To be honest, people coming into this industry are money-driven. They’re not exactly pursuant to higher learning.”

Dover said this is a troubling fact, particularly in the case of veterans who have the GI Bill at their disposal to help pay for their college coursework. And those ranks are considerable. According to the Census Bureau an average of one in 10 drivers served in the military, as did Dover.

“There are military personnel out there that come fresh out of the service and they get into truck driving — and they have the GI bill laying around,” he said. “I strongly recommend it to all military people to use that to their benefit, because it’s not that hard to get your degree and drive a truck at the same time.”

Dover’s own experience with the military predates his stint in the Navy (2007 to 2012). His father, Terry, was in the Army for most of Dover’s childhood, and he grew up in Germany. Living in Europe, he didn’t get the bug to drive trucks until he enlisted.

“The military actually introduced me to driving a truck,” he said. “Being raised in Germany, truck drivers — while they do have them over there — it’s not exactly a common occupation, I should say.

“I first learned how to drive a truck when I was stationed in Sigonella, Sicily, in the Navy,” he continued. “I first learned to drive on a 13-speed Mercedes. I fell in love with it as soon as I got behind the wheel.”

Following his Navy hitch, Dover earned his commercial driver’s license and began the life of a professional driver in 2012. Now with his fourth carrier, Central Oregon Trucking Co., Dover said he’s seen plenty of logistical nightmares through his previous work experience. Seeing how common these issues were for his fellow drivers inspired him to do something about it, and earning his degree is the first step in that process.

“I see the drivers around me, and I was looking into how we were treated as people, as drivers,” he said. “For instance, there’s lots of down time where drivers are having to sit at truck stops for hours, sometimes days on end without their next load. When our wheels aren’t turning, we’re not making any money.”

“I wanted to figure out a way to make a difference where drivers are treated better than what they have been and currently are,” he explained. “For me personally, Central Oregon is one of the best companies I’ve ever worked for, but I still want to be able to get out there and change the industry to help out my fellow drivers.”

Dover started out on an online business degree from Southern New Hampshire University when he had his accident. During the resulting downtime, he started exploring other educational offerings and found American Military University.

“They have this course that’s specifically tailored towards transportation and logistics. That was more my calling right there,” he said. “I figure being an operations manager, having that as a goal, would possibly be a stepping stone to very ambitiously being able to change the game, so to speak.

“Knowing that I’ve been behind the wheel for so many years, I can get my degree in logistics and transportation and hopefully be able to make a change for the better,” he said. “I know it’s not going to be an overnight thing and it’s going to be years’ worth of work, but I still want to try.”

Another motivation for Dover to further his education is closer to home: He wants to set an example for perseverance and commitment for his 9-year-old daughter.

“I hope that she is eventually able to find something that she can be passionate about that drives her to where she wants to make something of herself in it, whether it’s music, art, maybe even driving a truck,” he said. “Whatever she decides to do later on in life, as long as she’s 100% committed to it, the commitment and the pride in what you do is what I hope she achieves.”

Dwain Hebda is a freelance journalist, author, editor and storyteller in Little Rock, Arkansas. In addition to The Trucker, his work appears in more than 35 publications across multiple states each year. Hebda’s writing has been awarded by the Society of Professional Journalists and a Finalist in Best Of Arkansas rankings by AY Magazine. He is president of Ya!Mule Wordsmiths, which provides editorial services to publications and companies.