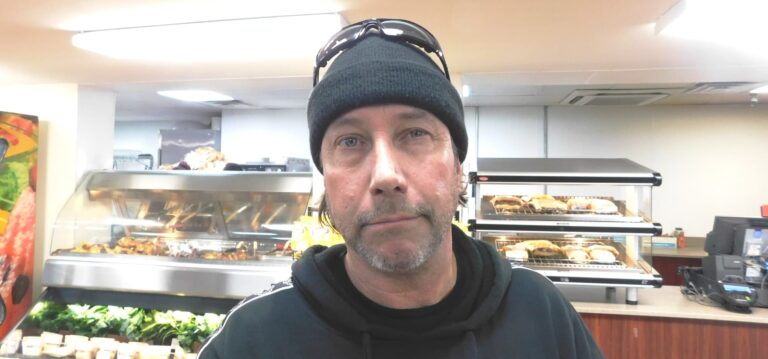

Standing at the grill counter, picking out the side dishes to his early afternoon meal, Thomas Bast seemed to be in no particular hurry. Or at least he didn’t seem like a man who felt rushed. He chatted a bit with the woman who was putting together his meal, and once he had his Styrofoam container in hand, he turned casually, in no great rush to get back to his truck.

Did he have time to talk? Yeah, sure, he could spare a few minutes. After 31 years behind the wheel, he wears his experience. You can see it in how he carries himself, taking his days in stride.

Just don’t get him going about ELDs.

Bast has seen a lot of changes to the business, and for his money there has been a decided turn for the worse in the last few years, and the reason? “This,” he said, tapping his finger on a picture of an ELD.

“These ELDs are a joke,” he said, “and they’re here to stay.”

Of course, the popular argument is that it’s not the ELDs, it’s the rules they are designed to monitor. But it’s the technology, Bast argues, that brings out the rigidity in those rules.

“The trucking industry is the most regulated industry in the country,” Bast said. “You have to be safe, that’s understood. But the more you regulate, it’s like choking” drivers who are trying to do their jobs.

“You can’t control what goes on outside your windshield,” he said. “You got roads, traffic, weather conditions. You’ve got four clocks to follow that don’t abide by any of those conditions at all.”

A prime example, he says, is the premise that he must take a 30-minute break “not before five hours and not after eight.”

“Listen, you got to be safe, right? We all know when to stop. Eleven hours is enough, a 14-hour day is long.”

Drivers know what they’re doing, Bast said, but the world doesn’t always cooperate with your schedule, and with paper logs, a driver could stretch the truth sometimes. Now, he said, the ELDs and other technology track drivers so closely it feels like a game of “Gotcha!” — a big money grab.

“They can fine you for talking to a dispatcher when you’re off duty, and they do,” he said.

“Now, what’s happening is you got truck stops filled up at 5 o’clock in the afternoon. You got guys sleeping on the side of the road. You’ve got troopers knocking on the window in the middle of the night who don’t care if they’re going to put them into violation; they got to get them off the side of the road.”

You didn’t see so much of that two years ago, Bast said. As he sees it, the emphasis on safety has actually cut into efficiency in the industry. Eventually, he said, we’ll all see the effects in higher prices for, well, everything.

“You got to be safe,” he said, “but you got to get out of the way more.” He even questions whether we’re really getting safety.

“You think this is going to slow them down?” he said. “It’s going to speed them up, because they got to get to the truck stop, got to get to that break, got to pull over.”

Bast, 52, became an over-the-road trucker at 21. He came to trucking by horse, racehorses, to be exact.

“My family was in the equine business,” Bast said. When he was young, he shoed horses. From there, he progressed to transporting them. When the family business folded, he moved from horses to horsepower, moving racecars.

Throughout his career, Bast has specialized in enclosed car transport, moving racecars, antiques and exotic cars. “Lambos, Ferraris, Bugattis … ,” he said. He’s a private contractor currently with United Routes Transport.

“I never did general freight,” Bast said. “I never ran by the mile. I always specialized, because that’s where you make good money.”

Still, the time restrictions matter. His contracts call for a percentage of the gross receipts of the truck. “When you broker a deal it’s three to five days, five to seven, or seven to 10 days. And when you don’t hit those deadlines, it comes off your gross receipts,” he said.

Being out on the road five or six weeks at a time, Bast said he’s pulling in about $90,000 a year, and he pretty much gets to call his own shots, professionally speaking, which goes a long way in offsetting his frustrations.

He’s also a little concerned about the driver shortage, or rather the reaction to it. “They’re spitting guys out of those schools that don’t know a steering wheel from a fifth wheel,” he said.

“A lot of these guys are because they were middle management, they lost their job in ’08, and this was the easiest thing to jump into. When I started, you were there because you wanted to be there.”

He still does, but after more than three decades doing it, he’d be a lot happier if there was a little more trust that he knows what he’s doing.

And with that, he excused himself. He had to get going.

Klint Lowry has been a journalist for over 20 years. Prior to that, he did all kinds work, including several that involved driving, though he never graduated to big rigs. He worked at newspapers in the Detroit, Tampa and Little Rock, Ark., areas before coming to The Trucker in 2017. Having experienced such constant change at home and at work, he felt a certain kinship to professional truck drivers. Because trucking is more than a career, it’s a way of life, Klint has always liked to focus on every aspect of the quality of truckers’ lives.