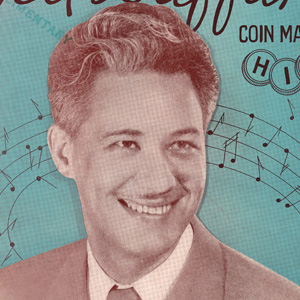

Louisiana-born Ted Daffan (1912-1996) had already made his mark as a singer/songwriter in southeast Texas when he pulled into a roadside diner one evening in 1938.

Little did he know the diner would inspire a new song — a short, simple tune that would make Daffan a pioneer of a new category of American music. Historians agree that when Ted Daffan went home and penned the lyrics to “Truck Driver’s Blues,” he gave birth to “truck-driving music,” a genre that lives on 82 years later.

The irony of the background to “Truck Driver’s Blues” is that Daffan’s simple observations and simple lyrics satisfied the needs of a society in the grips of the Great Depression, a society for which simplicity was a luxury. In the process, the song also made Ted Daffan quite wealthy for a musician of the time.

After graduating from Lufkin (Texas) High School in 1930, Daffan taught himself to play the Hawaiian guitar, the metallic sound of Hawaiian music catching his ear. By 1933, he played well enough to land a spot with The Blue Islanders, a band with a regular radio show on Houston’s KTRH. When The Blue Islanders folded, he played with other bands such as The Blue Playboys and The Bar-X Cowboys, signaling a movement toward western swing.

Daffan held an interest in electronics, particularly how they could be used to improve instrumental music. During the 1930s, he experimented with amplified guitars and operated a shop in Houston specializing in electrical instruments. By the end of the decade, Daffan and his amplified steel guitar blazed a new trail in western swing, a style of music previously known for its use of twin fiddles. The steel guitar put the “twang” in western swing — and eventually in mainstream country music. Today the instrument is regarded as one of most difficult to master.

But Daffan was ahead of his time.

Daffan considered himself a songwriter first and a performer second. “Truck Driver’s Blues,” the song for which he is arguably best remembered, took shape two years before he began a serious recording career. Daffan turned to fiddle-playing bandleader Cliff Bruner with his song, hoping Bruner and his Texas Wanderers could make it suitable for airplay. Likewise, Bruner had a contract with Decca Records, the label that gave Bing Crosby his break in the music business.

History proves Daffan made a wise choice.

The story of “Truck Driver’s Blues” is almost too perfect to be anything but a legend, but it is a story music historians repeat as factual. Daffan’s stop at the unknown roadside café, perhaps a precursor to the truck stops of later years, gave him the chance to observe several truck drivers. As Daffan waited for his meal he watched, as one after another, the drivers parked their rigs andentered the diner. Before sitting down, every driver stopped at the jukebox, put in a couple of nickels and hung around to hear a favorite tune.

Realizing that Depression-era truck drivers willingly spent five or 10 hard-earned cents on something as simple as a song gave Daffan an idea. What would truck drivers pay if one of those songs in the jukebox focused on the drivers themselves? As the story goes, Daffan saw dollar signs — or at least a lot of nickels — all destined for his pockets.

A few hours later he penned what would become the first truck-driving song. When the Texas Wanderers recorded “Truck Driver’s Blues” in early 1939, it was an instant success. In the early days of country music, a major hit sold about 5,000 copies. Released on the Decca Records label, “Truck Driver’s Blues” was not only the top-selling record of 1939, but it also sold a staggering 100,000 copies. Ted Daffan had indeed struck a chord with a new audience, and in the eight decades since, many songwriters and performers have made their marks on music following Daffan’s lead.

“The blues” had been around a lot longer than Ted Daffan. In the first few decades of the 20th century, the blues, a music genre thought to have originated in Africa, became mainstream. The Great Depression was a period when most Americans had a case of the blues, and the songs of the 1930s are nothing less than a musical history of the years of poverty. Whether the blues performers sung of breadlines, tax collectors, the Dust Bowl, prohibition, Wall Street, milk cows or perhaps the most collective, “The All In and Down and Out Blues,” the songs struck the collective nerve of society. Daffan recognized the same look of “the blues” in the faces of truck drivers.

More than 80 years after The Texas Wanderers recorded “Truck Driver’s Blues,” the lyrics are just as applicable as they were in 1939. Drivers of the 21st century may travel America on controlled-access highways designed for speed rather than the winding two-lane roads following pig trails of days gone by, but the worries of yesteryear remain alive in the trucking industry.

Like many blues-related songs, “Truck Driver’s Blues” begins with a familiar line of misery, “Feelin’ tired and weary.” Beyond those opening words, however, Daffan sums up the life of a truck driver in just three short phrases:

“Keep them wheels a-rolling, I ain’t got no time to lose.

There’s a honky-tonk gal a waitin’ and I’ve got troubles to drown.

Never did have nothin’, I got nothing much to lose — just a low-down feelin’, truck driver’s blues.”

Those sentiments, the same truck drivers have today, are what “Truck Driver’s Blues” put to music — no time to lose, troubles to drown and nothing left to lose (other than the blues).

“Truck Driver’s Blues” is a simple song written in simple times. And as Daffan discovered after an evening in a roadside café, satisfying Americans’ simple desires through simplicity itself can be lucrative — and groundbreaking.

Until next time, when you’re feeling tired and weary, stay safe and pull off the highway. Staying safe can keep the blues at bay.

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.