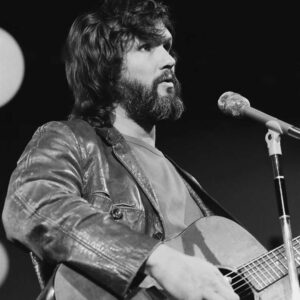

When it comes to performers, the connection between singer and songwriter is not just important — it is an absolute must. Since country music was born a century ago, it has become America’s heartbeat, and its lyrics pay tribute to American values in a way no other musical genre can rival. When a singer, a songwriter and a song fail to connect, the result is like a sore thumb on the airwaves. It’s hard for any performer to replace the passion a songwriter puts into lyrics based on personal experience. That’s why the country’s iconic artists often write their own songs. When it comes to writing from the heart, no one ever put the lyrics of his life to music better than “The Hag,” Merle Haggard.

Haggard was a Depression-era baby, a true child of the Dust Bowl. Along with other families moving from Middle America to California in search of a mythical lifestyle, Haggard was the son of “Okies,” his parents relocating to the West Coast to escape the Oklahoma drought. Haggard drove that point home point decades later with his 1968 signature song, “Okie from Muskogee.” But he was more than an Okie. Haggard was a working man — a blue-collar, flag-waving, right-winged performer whose music appealed to the millions holding similar values at the height of the cultural shift of the 1960s.

Young Haggard did little to overcome the hard lot he drew in life. He spent years in juvenile detention facilities and eventually wound up in San Quentin State Prison, mostly for minor but habitual offenses. By the time he left prison for good in 1960, he had a new attitude, knowing that another misstep could send him back for good. In true blue-collar style, Haggard assumed what is often joked about as the lowest of jobs — ditch digger. In his spare time, he pursued music, writing songs that recounted his life and experiences. By 1970, Haggard had climbed the charts to become one of the most famous musicians in America.

In 1974, America’s oil embargo shined a spotlight on one of the blue-collar jobs Haggard paid tribute to in his songs, the truck driver. At the time, drivers were on the verge of national heroism and enjoyed status as cultural icons in the U.S. In fact, it’s hard to discuss 1970s culture without at least casually referencing truck drivers and the “fans” passing them on the interstates begging for the satisfying air-horn salute. It was only natural that Hollywood seized the moment to propel truck driving even higher in the public consciousness.

In 1973, producers Barry J. Weitz and Philip D’Antoni (a 1973 Academy Award winner for “The French Connection”) pitched the NBC network on a television movie capitalizing on the public’s interest in truck driving. In May 1974, their idea aired as “The Tandem,” starring Claude Akins and Frank Converse as independent truck drivers Sonny Pruitt and Will Chandler. The movie’s plot focused on a pair of rogue drivers coming to the aid of citrus growers exploited by the agriculture industry. “The Tandem” was received well enough that NBC signed Akins and Converse on for the ensuing series, “Movin’ On,” that debuted in the fall of 1974.

Theme songs were all the rage in 1970s television. A good theme song went a long way toward making a series successful. Weitz and D’Antoni knew “Movin’ On” had to connect with a blue-collar audience. They also knew no singer in America connected to the “working man” more successfully than Merle Haggard.

When offered the chance to write and perform the theme to “Movin’ On,” Haggard wasn’t sure he was right for the job. As a singer-songwriter, he had become successful because he’d lived his lyrics. Since recording his first No. 1 Billboard Country single in 1966, Haggard had released 27 singles, 22 of them hitting No. 1 and the other five rankings no lower than No. 3 on the charts. Writing a song with a predetermined title for a TV series with a predetermined plot was like nothing Haggard had done musically. Perhaps the idea offered a challenge he couldn’t resist. But more likely, Haggard realized that the theme song, no matter if it ever reached radio, guaranteed him a national audience of millions of television viewers at least one night a week on television at precisely 8 p.m. Eastern time.

Haggard decided to write the song like he would one about his own life, only he wrote through the eyes of an observer of the show’s fictional characters. In fact, he makes reference to “Will and Sonny” in the lyrics. The words pay homage to truck drivers and the work they do, with a special emphasis on the importance of the trucking industry in the phrase, “The white line is the lifeline of the nation.”

While “Movin’ On” only lasted two seasons on television (44 episodes), it served as a precursor to the CB radio craze and other truck-driving cultural icons such as C.W. McCall and his massively popular song, “Convoy.”

As for Haggard, the brief popularity of “Movin’ On” forced him into a situation of recording and releasing the song as a radio single. He did just that in 1975, and “Movin’ On” joined the likes of “Sing Me Back Home,” “Mama Tried” and “If We Make It Through December” as a No. 1 Merle Haggard recording. While it may not be remembered as Haggard’s most popular song, “Movin’ On” was one the public begged for in the mid-’70s, and Haggard did not disappoint his audience.

Until next time, make sure the only fever you run is for “jamming gears,” and stay safe as you prove Haggard’s words to be true. Truck drivers are truly the “lifeline of the nation.”

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.