By the late 1970s, Mickey Gilley was a bona fide country music headliner. But he couldn’t have imagined what lay in store for him as the decade ended, even as a hint of the success he was about to enjoy came from a 1977 song by his famous cousin Jerry Lee Lewis.

The next to the last of Lewis’ string of Top 5 singles came by way of his No. 4 hit “Middle-Age Crazy.” The plot of the lyrics revolves around a successful businessman’s mid-life crisis. Despite his success, something is missing from his life. To deal with growing older, he remakes himself. As Lewis sang, he traded his business suit for “jeans and high boots with an embroidered star.”

Neither Lewis nor Gilley realized that the minor hit set the stage for a cultural shift in the U.S. “Middle-Age Crazy” was released as a movie starring Bruce Dern in early 1980, but it largely failed at the box office. However, the motion picture’s theme was about to become ingrained in American culture.

The “cowboy look” soon became the American style of the early 1980s — only it wasn’t Lewis who helped bring cowboy dress to the forefront. Instead, it was Gilley, with a healthy dose of John Travolta, who led the revolution.

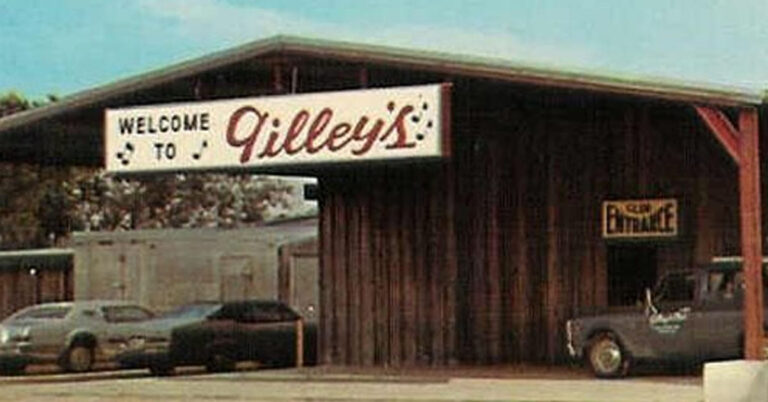

When producers of the movie “Urban Cowboy” looked for a location to shoot their film, they knew they needed a country nightclub, and a big one. The so-called largest honky-tonk in the U.S., Gilley’s Club in Pasadena, Texas, offered the perfect backdrop. John Travolta, who was fresh off starring in the anything-but-country motion pictures “Grease” and “Saturday Night Fever,” found himself cast in the role of country boy Bud Davis, a young man who relocates to the Houston area and starts frequenting Gilley’s club.

Looking back over four decades, the plot of “Urban Cowboy” is easily forgotten. But for those who lived through the era it ushered in, the movie’s impact is hard to forget.

Gilley and several nightclub employees had parts in the movie, and Gilley’s band provided much of the soundtrack. Gilley himself was featured on the soundtrack album. “Here Comes the Hurt Again” brought Gilley a lot of air play — but it was his countryfied rendition of the soul song “Stand by Me” that elevated him from being an occasional hit maker to one of the 1980s most prolific artists.

Likewise, it was Gilley’s style — cowboy boots, western hats with feathered grommets, and just a general western style of dress — that became all the rage. Areas of the country like New England, where few followed country music and only a handful of true cowboys lived, were suddenly overrun by Yankees donning the “Urban Cowboy” style. The period did much to increase the popularity of country music nationwide, and western retailers popped up from coast to coast.

In short order, the image of the “Urban Cowboy” shifted from John Travolta’s character to the real-life Gilley. Gilley’s nightclub became a sensation and spawned the opening of similar country clubs across the nation. It also created an environment in which one of country music’s most popular female singers, Barbara Mandrell, could record her signature song, “I was Country (When Country wasn’t Cool).”

By the time Gilley’s career slowed down, he had charted 39 Top 10 singles, 17 of which reached No. 1. The likes of “You Don’t Know Me,” “That’s All that Matters to Me” and “True Love Ways” became classics of the 1980s country era. As the decade passed, Gilley shifted his music to a more orchestrated style, featuring strings and his iconic piano in his recordings rather than the hard-driving piano of his earlier sons like “The Girls All Get Prettier at Closing Time.”

This fresh Gilley style was largely inspired by the crossover success many country artists experienced during the decade. The change in his music also reflected a change in Gilley’s persona. The man who had ridden a nightclub to fame made himself over for a new audience. He sold his nightclub and relocated to a new spot in the U.S. where country music was taking off — Branson, Missouri.

Branson was a growing community that centered around country music-related entertainment. For a performer like Gilley, the area was a godsend. The city became packed with theaters and boasted as many current and former stars per square mile than anywhere other than Nashville. And the town became a saving grace for more than one artist’s career.

“Branson works because it provides the best conditions for the fans and the entertainers,” Gilley said. “The fans get to see us under the best setting possible … theaters have good seats, and we have the best stage setups.”

What’s more, performers in Branson often owned their theaters. They didn’t have to deal with the daily grind of putting together and tearing down a stage show. The grueling pace of touring didn’t wear down the performers, most of whom owned homes not far from their theaters. Throughout the 1990s, Branson grew, and Gilley found himself at the center of another seismic shift on the country music scene. He became one of Branson’s most popular stars, raking in profits from hundreds of fans who’d visit for both afternoon and evening shows held year-round.

While the new hits stopped coming when Gilley shifted to Branson, the audiences his show attracted didn’t seem to care. Promoters marketed Branson toward an older crowd — people who remembered the likes of Andy Williams, Floyd Kramer, Mel Tillis and numerous comedy and variety shows. These people didn’t expect or want to hear new material from the performers whose shows they frequented; they wanted to hear the hit songs of days gone by.

Gilley’s former popularity provided enough hit songs to fill a show, and recording wasn’t as important as it had been earlier in his career. Branson became a prime retirement area for people looking for a nice place to live, and it served semi-retired performers as well.

For the most part, Gilley played out his life in Branson. His shows were among the most popular in the city. Gilley’s name became as much a part of Branson as the ever-popular theme park Silver Dollar City. And it provided an iconic setting for a popular artist to complete a career that headlined two of the most noted contributions to late 20th century country music.

Until next time, don’t wear a cowboy hat in a Ford Focus. It just ain’t right.

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.