If you ask truckers about the most important things in their lives, some might say that right after family, God and country, their truck’s brakes are close to their hearts. After all, both their livelihood and their lives rely on those brakes functioning properly.

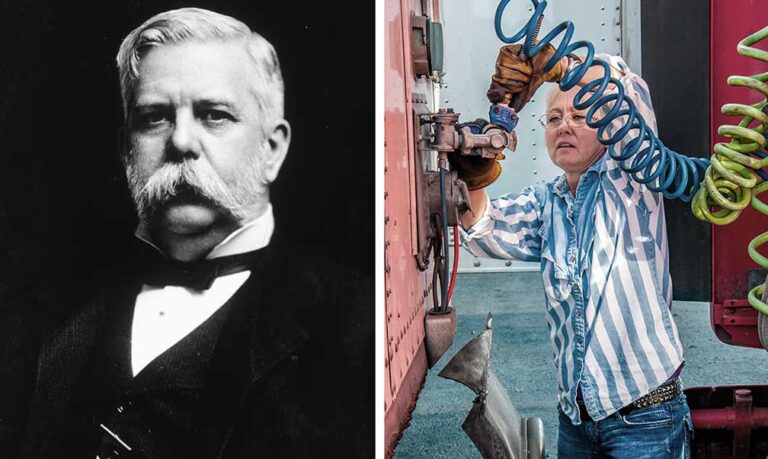

While it’s true that everything in motion will eventually come to a stop, it’s important to be able to control when and where those stops take place. Since 1925, when air brakes became standard on trucks, credit for helping trucks stop is given to George Westinghouse.

But his invention came long before trucks — or even horseless carriages — traveled the roadways.

If you want to get scientific about the matter, no one “invented” brakes.

Braking is a matter of physics, most notably friction and gravity. Since the first rock rolled down a hill, Mother Nature had a way to bring it to a stop. It was up to humans to harness that friction and make it work to their advantage.

And that’s just what George Westinghouse did way back in 1868. Yes, I’m talking about the George Westinghouse of Westinghouse Electric.

Westinghouse was born in 1846 in Central Bridge, a small community in New York state. His father, a farmer and machinist, planted an interest in technology in young Westinghouse, but other matters had to be tended to first.

At the age of 15, just after the outbreak of the Civil War, Westinghouse enlisted in the New York National Guard, largely against his parents’ wishes. Later he served in the New York Cavalry, and eventually in the Navy. At war’s end, the still-young Westinghouse enrolled in college … but he quickly found the strict rules weren’t right for him.

You might say the 19th-century version of STEM education didn’t sit well with Westinghouse’s style of learning. He was an inventor — and invent he did.

Before Westinghouse reached the age of 20, he secured his first patent on a rotary steam engine. He followed this invention by developing a method of rerailing railroad cars after they had derailed. From that point, he largely became noted for his involvement in transportation, most notably the railroad.

Before the advent of gas-powered vehicles, there were steam-powered locomotives.

In the mid-1800s, stopping a train was dangerous work. Each railroad employed brakemen whose job it was to run along the railroad cars and manually apply the brakes to each one. Over the years, thousands of brakemen were killed on the job, and the railroad could not be as efficient as its potential because brakemen could operate brakes on less than a dozen cars at a time.

Westinghouse decided there had to be a better way. His solution was the air brake — and the Westinghouse Air Brake Company was born.

Westinghouse’s air brake system was not complicated in design. A compressor located in the locomotive connected to a reservoir and valve fitted on each car.

Rather than brakemen swinging between the cars, a steam pipe ran the length of the train. This pipe, which flexed between cars, controlled the brakes and refilled the reservoirs. Engineers could control all the brakes from the locomotives with one maneuver.

Over the next few years, Westinghouse improved his air braking system. In the meantime, he worked on other projects ranging from natural gas to electricity to shock absorbers.

Westinghouse’s air brakes soon became standard equipment on trains both in the U.S. and Europe. Its popularity grew in 1895 when the federal government required the Westinghouse brake system on all future trains.

Then came the advent of the “horseless carriage,” which also required braking devices.

By 1905, more than 2 million automobiles were fitted with air brakes. Further improvements to the system continued well beyond Westinghouse’s death in 1914.

In 1922, as trucks gained in popularity following World War I, the air brake system was used for larger trucks hauling heavy loads. By 1925, Westinghouse’s air brakes were generally accepted as standard on all trucks.

The alternative to the air brake system has long been hydraulic brakes, like those typically found in modern passenger vehicles. Unlike air brakes, hydraulic brakes are operated by compressing fluid, and the fittings are more likely to leak and result in brake failure.

As those following Westinghouse noted: Air is always available to be compressed; but hydraulic fluid must be found and poured into the braking system.

Today’s air braking system includes a compressor, governor, reservoir tanks, a dryer and drain valves, along with the foot valve (better known as the brake pedal). Of course, 18-wheelers are fitted with separate braking systems — one for the tractor and another for the trailer.

Modern air braking systems are more sophisticated than their predecessors.

In the heavy-duty truck industry, air brakes are more complicated than those original systems Westinghouse initially invented for trains — and they are also more fail-safe. Backup systems kick in when primary brakes fail, something that adds an extra level of safety when a driver wants to stop a truck. Both tractors and trailers are fitted with parking brakes as well. When released, the brakes offer the familiar “whoosh” sound that so often announces a large truck is in the area.

George Westinghouse perfected the air brake system for use in the industrialized world. Air brakes have survived the growth of technology, and the essential components of Westinghouse’ original design remain more a century and a half later.

In the end, a college dropout with a mind for inventing and entrepreneurship, set the stage for a safe, effective method of operating commercial vehicles.

It can be said quite literally that Westinghouse continues to bring traffic to a stop.

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.