The year 2020 will long be remembered for the COVID-19 pandemic and the chaos it brought to the economy, business and our lives in general. Something else the year will be remembered for is that it was the first full year after regulations for electronic logging devices (ELDs) were implemented.

The devices fundamentally changed the trucking industry. Whether most of the changes were beneficial or accomplished the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s (FMCSA) goal of “creating a safer work environment for drivers of commercial motor vehicles” is a matter of much debate.

To be sure, ELDs were here long before the Dec. 19, 2019, compliance date. Regulations introducing the predecessor to the ELD, the automatic onboard recording device (AOBRD), were published in 1988. By the year 2000, attempts by the FMCSA to mandate use of the devices had already been defeated in court order. A rule published in 2010 allowed the agency to mandate ELDs for carriers that have poor compliance records.

In 2012, however, Congress acted to require the use of ELDs by law. As a part of a highway funding bill, MAP-21 (Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st century), the FMCSA was required by law to mandate ELDs. After conducting a number of studies, the rule was published in December 2015.

Dec. 18, 2017, was the deadline for most carriers to implement ELDs. Carriers that had invested in AOBRDs were given an additional two years to switch over to ELDs, with Dec. 16, 2019, as the date for full compliance.

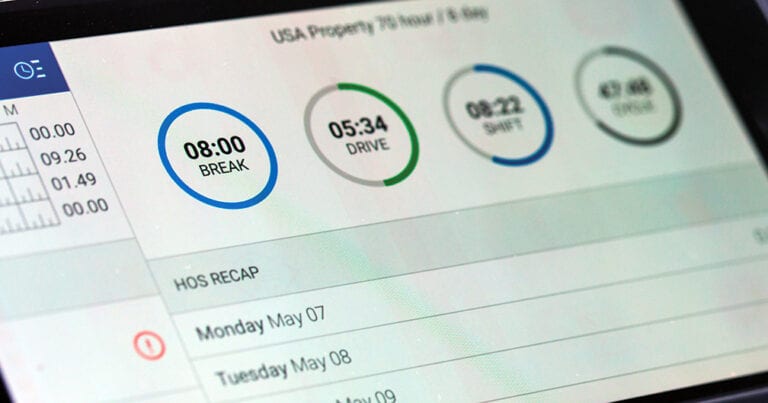

The FMCSA soon reported that, as predicted, compliance with hours-of-service regulations had improved considerably. Drivers who had previously been able to manipulate their record-of-duty status (RODS) on paper logs (often at the behest of the carriers they worked for) found it more difficult to do so with ELDs that recorded truck movements. Carriers spent less time auditing piles of logbook pages submitted by drivers. But then….

Carriers began to experience what drivers had been telling them all along. Productivity plummeted when drivers used ELDs. For example, drivers, who were taught to “save” as many hours as possible by recording waiting time at shippers and receivers as “off duty” could no longer do so, because the ELD started the 14-hour clock as soon as the truck moved. On-duty time increased dramatically, and many drivers found that those extra on-duty hours ate into their available driving time.

Drivers who are compensated by the mile saw their earnings drop. At the same time, carriers could no longer count on established transit times and were forced to adjust schedules and deal with service failures caused by the changes. Some imposed strict time requirements on shippers and receivers to minimize the issue.

ELDs also had an impact on driver retention. The industry was already experiencing an aging driver fleet, with the average driver age getting closer to 50 each year. In many cases, drivers who were close to or past retirement age — and unhappy over reduced income and increased oversight — decided to leave the industry. Other drivers chose careers in other fields.

With the mandatory use of ELDs and, at many carriers, the use of inward-facing camera systems that record the driver’s every action, new drivers are becoming harder to attract. A profession that traditionally attracts independent-minded individuals to work with a minimum of supervision is hemorrhaging drivers due to perceived micromanagement.

Another unintended consequence of the ELD mandate was a boom in sales of

pre-2000 model year trucks, which are exempt from the ELD requirement. By law, ELDs must connect to the vehicle’s electronic control module, which records details of vehicle operation. Prior to 2000, many vehicles operated entirely by mechanical means or had simpler computer systems that did not retain operational information.

Some truck manufacturers had been offering “glider kits” — essentially new trucks without powertrains — and relying on dealers to install pre-2000 components that were usually rebuilt before installation. While these kits first appeared as cheaper alternatives to brand-new vehicles, they gained popularity for other reasons: The older engines were exempt from some of the Environmental Protection Agency’s unpopular emissions regulations that were imposed between 2000 and 2010, in addition to exempting the driver from ELD use.

Sales of trucks based on glider kits grew exponentially as carriers and independent owners sought to avoid the pitfalls of both newer engines and ELDs.

Perhaps most importantly, the safety benefits promised by ELDs didn’t materialize. As the miles traveled by large trucks and buses increased each year, so did the number of those vehicles involved in crashes, according to FMCSA statistics.

In 2015, before ELDs were mandated, the number of large trucks and buses involved in fatal crashes per 100 million miles traveled (by ALL motor vehicles) was 0.140. That number increased to 0.151 in 2016, then to 0.157 for both 2017 and 2018. The total number of fatalities reported in crashes involving large trucks or buses was 0.125 per 100 million vehicle miles in 2015. The following year it rose to 0.138, then to 0.143 for 2017 and 2018.

The FMCSA data did not include numbers for 2019 and 2020. Numbers for 2020 will likely be impacted by greatly reduced traffic due to the economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reasons for higher crash numbers vary, but many drivers point to the lack of flexibility in the regulations. With the 14-hour clock rigidly enforced, for example, drivers who lose time waiting at docks find themselves hurrying, and sometimes speeding, to drive the required number of miles before time runs out on their shift.

In another example, the practice of avoiding peak congestion times in metropolitan areas allowed drivers to record a break (off-duty) or even a nap (sleeper berth), and then continue their journey later when traffic cleared. With the 14-hour clock ticking away on the ELD, those breaks now use up driving time. This forces the driver to keep going, increasing the risk of an accident while losing more valuable time stuck in a line of traffic.

Without the intervention of Congress, it’s doubtful ELDs will go away any time soon.

Efforts were made by the FMCSA to relax some HOS regulations, including changing the conditions of the mandated 30-minute break and allowing more flexibility in split sleeper definitions, and a pilot program exists that would allow drivers to “pause” their 14-hour clock. With a new administration in Washington, however, further attempts to relax current HOS rules may not be welcome.

When government attempts to fix a problem, unintended consequences often occur. That’s certainly true of the ELD mandate.

Cliff Abbott is an experienced commercial vehicle driver and owner-operator who still holds a CDL in his home state of Alabama. In nearly 40 years in trucking, he’s been an instructor and trainer and has managed safety and recruiting operations for several carriers. Having never lost his love of the road, Cliff has written a book and hundreds of songs and has been writing for The Trucker for more than a decade.

By “save”ing hours you mean cheating the rules? LOL Productivity of those drivers forced to run 80-90 hours or more a week sure did drop, but the majority of companies, dispatchers and drivers have seen productivity increases with ELDs and GPS tracking. Those 80-90 hour guys probably have a better work/life balance as well, once they get used to it…or retire if they can’t. Shippers and receivers need to be on the ball with scheduling/loading or find someone running a glider to haul their stuff in violation of the rules. Good luck with that. The sleeper and 14hr rules certainly need more flexibility for the reasons you cite, hopefully the new Administration realizes that, but as they are beholden to the unions I doubt they’ll take any positive action for drivers on them.

The electronic logs did put a damper on dispatch. I have been in the transportation industry for almost 30 years. Done both safety and compliance and drove both over the road and local. I started in 1993 and shortly after is when a large company went to .42 a mile. The majority of my years driving it has been as an owner operator due to the fact that I have choices. It is similar to what the ELDs are doing forcing you to run compliant. To me truck driving is modern day slavery. What I mean by that is that before ELDs you could deliver at 8am and sit waiting all day for dispatch to send a load at 3pm that has to be 650 miles away by morning. If you say no you are the bad guy even if you explain you have been up all day waiting. The ELDs eliminated a lot of that and forced companies to get organized. When I brought up the pay earlier it was due to it hasn’t changed much for company drivers in 30 years. I understand that truck cost has gone way up as well as problems with all of the emission BS that is on them now (thanks calif.). There are some companies that pay very well but not most and they still try and get you to play games. The accidents going up is also due to the lack of training to for new drivers. It could be the training or lack of understanding by the potential driver due to a language barrier. Working local now not 70 hours a week and training new drivers for about 40-50 hours a week. The ELDs help in my opinion. Stay safe!