Electric vehicles (EVs) have been prominent in many recent transportation headlines, due in large part to their prominent role in the recently passed infrastructure act. As the nation moves toward its goal of zero-emission transportation, both for passenger and commercial vehicles, the government plans to spend millions on technology to support EVs, including the installation of charging stations along certain highway corridors and even in government housing.

But the universal adoption of electric vehicles — at least those using battery power — is not a foregone conclusion.

Hydrogen is another potential answer to reaching the goal of zero emissions. Hydrogen can be burned in place of fuels like natural gas or propane. It can also be used to power fuel cells that generate electricity to power electric motors, eliminating the need for heavy, expensive batteries. In fact, three auto manufacturers — Kia, Honda and Toyota — are already selling hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicles in the U.S.

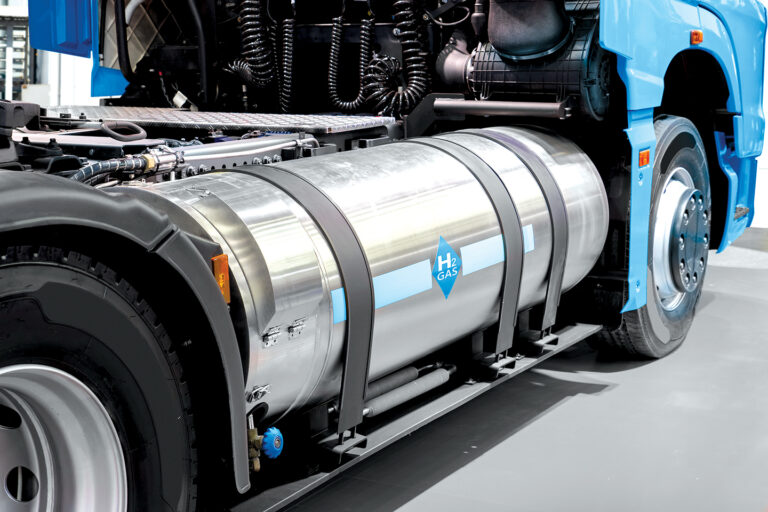

Hydrogen fuel cell technology is being explored for use in commercial vehicles, too. Cummins, a name long familiar to diesel engine buyers, introduced a hydrogen fuel cell at the 2019 North American Commercial Vehicle Show in Atlanta, Georgia. The company is currently working with OEMs to produce trucks, buses and even trains that operate with fuel cell electrification.

An August 2021 study published by Information Trends, “Global Market for Hydrogen Fuel Cell Commercial Trucks,” predicts that more than 800,000 hydrogen fuel cell commercial vehicles will be sold by the year 2035.

“In the long run, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles will dominate the market for trucks and commercial vehicles,” the report claims.

According to the study, battery-electric commercial motor vehicles (CMVs) will have the advantage, at least until hydrogen fueling stations become more widely available and production costs come down.

Hydrogen power makes sense for trucking, because the systems don’t require heavy batteries that reduce cargo capacity. In addition, refueling times for hydrogen-powered vehicles are similar to those of diesel-powered equipment.

There are downsides to the use of hydrogen as a vehicle fuel, however.

A key issue is availability. A new electric charging station, for example, only needs to be connected to the existing grid. Large applications, such as trucking terminals, may require additional power lines, but the distribution system is already in place. Hydrogen, on the other hand, must be compressed and transported to distribution points.

Another current disadvantage of hydrogen is its energy efficiency. It takes electricity to create hydrogen, just as it does to charge a battery. The delivery and use of that electricity, however, consume some of the original power.

A June 2020 blog posting on The Conversation website predicts that “hydrogen cars won’t overtake electric vehicles because they’re hampered by the laws of science.”

The posting claims that, out of 100 watts of generated electricity, only about 80 watts end up being used to power the vehicle. The rest are lost in the processes of transmission to destination, charging and discharging a battery, and the conversion of electricity to mechanical wheel-driving power.

The process of producing hydrogen, however, uses about 25 watts of each 100 watts. Compressing and transporting the hydrogen uses more, and then more is lost as the fuel cell converts the hydrogen into electrical power. The end result is that only about 38 watts of the original 100 are used to power the vehicle.

So, while hydrogen fuel cells may be advantageous in the vehicle, the entire process of making the fuel available is far less efficient.

Since hydrogen can be burned as fuel, however, it can be used in the same way fossil fuels, such as natural gas, are currently used, potentially through the same distribution network. Hydrogen can be used for fuel in internal combustion engines, too.

Prince George, British Columbia-based Hydra Energy is using hydrogen to reduce diesel engine emissions right now. The company has teamed up with Lodgewood Enterprises to pioneer a device that allows a diesel engine to burn up to 40% hydrogen in the combustion mix. Hydra also supplies the hydrogen at a cost that is comparable to diesel fuel.

Currently the Lodgewood truck is making regular runs between Prince George and Edmonton, Alberta, a nearly 1,500-kilometer (932-mile) round trip.

The Hydra co-combustion device is retrofitted to an existing diesel engine and adds hydrogen, stored in tanks behind the cab, to the air intake of the engine. The resulting hydrogen-air-diesel mix reduces emissions by up to 40%.

Hydra’s hydrogen-diesel conversion kit is provided free of charge and is fully reversible if the need arises. The company worked with truck OEMs to ensure the product doesn’t void any engine warranties. Should the hydrogen tanks empty, the truck can operate on diesel fuel alone until the hydrogen can be replenished.

Hydra’s long-term goal isn’t the co-combustion kit; it’s distribution of the hydrogen that makes it work.

“We’re building our own hydrogen refueling station in Prince George, but it’s actually an integrated refueling system where we’ll have a diesel provider offer the diesel part and then that way the truck doesn’t have to go to two places” said Jessica Verhagen, CEO of Hydra Energy.

“This integrated fueling station means that they can fill up on diesel and hydrogen at the same time, in about the same time as filling the diesel up alone,” she continued. “And we’re already looking at another three sites beyond Prince George.”

Verhagen referred to BayoTech, an Albuquerque, New Mexico-based hydrogen producer that has announced plans to build 50 “hydrogen hubs” by the end of 2024. She’s also seen hydrogen availability increase for automobile drivers.

“You can see hydrogen being added, for example, at the Shell station close to where I live,” she noted.

Hydrogen fuel cell technology isn’t something Hydra Energy is working on, but a network of fueling stations built for trucks equipped with the company’s co-combustion kit could easily become the supply point for fuel cell-equipped trucks in the future. For now, the retrofit makes it possible for fleets to reduce emissions without investing in new vehicles.

“A typical truck sold today has an expected lifetime of 15 to 18 years,” Verhagen explained. “So, if people are still buying internal combustion engines today, they may want to do something with their existing fleet instead of waiting for replacements.”

No one knows for certain which technology will replace diesel fuel to power the trucking industry, but chances are good that hydrogen will be in the mix.

Cliff Abbott is an experienced commercial vehicle driver and owner-operator who still holds a CDL in his home state of Alabama. In nearly 40 years in trucking, he’s been an instructor and trainer and has managed safety and recruiting operations for several carriers. Having never lost his love of the road, Cliff has written a book and hundreds of songs and has been writing for The Trucker for more than a decade.