When it comes to trucking songs of the “golden era” (1963-1977), songwriters were, for the most part, inspired by locations or experiences in the South, Midwest and on the West Coast. Most of the artists recording the songs hail from the same areas, although Canada has offered up a few trucking songs receiving U.S. radio airplay. But even Canada, where U.S. country music has a large following, has likely inspired more songs than its neighbor — Maine. A full-time country radio station of note didn’t even exist in the state until 1967. Even today, the number of nationally recognized country artists native to Maine can be counted on a few fingers. Dick Curless, a trucker turned musician, has yet to be surpassed as the most successful.

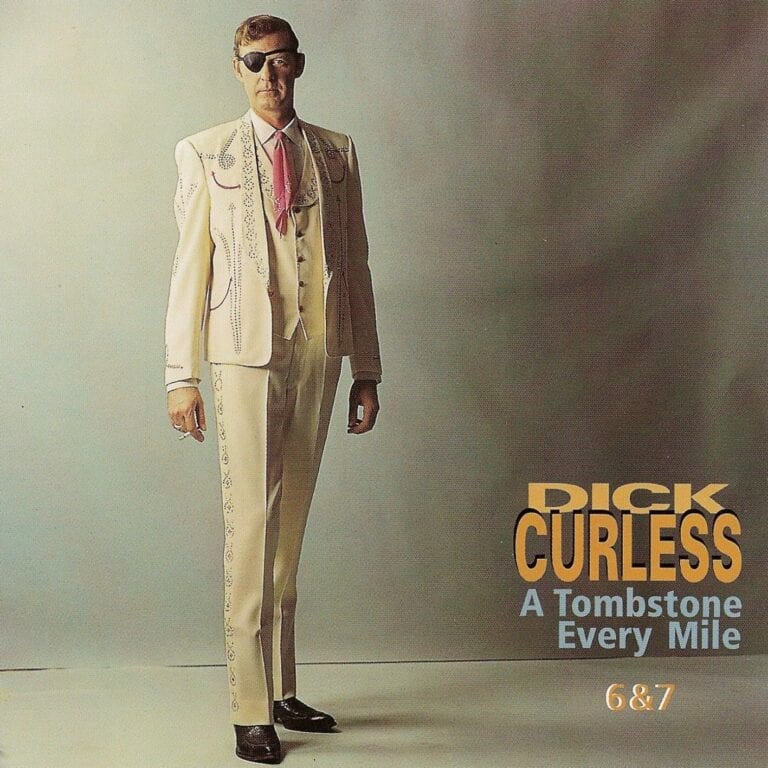

Dick Curless was born in 1932 in Fort Fairfield, Maine. Today, Fort Fairfield is a hamlet of 120 residents in the secluded northeastern area of the state bordered to the east by New Brunswick, Canada. Before turning 10-years-old, Curless’ family relocated to Massachusetts, where in 1948 he began his music career with a local band. A few years later, he was in Korea driving an Army truck and known to soldiers as “The Paddy Ranger” on Armed Forces Radio. Upon returning to Maine, Curless didn’t immediately resume singing, instead buying a truck to haul timber. He did eventually return to the stage, his stature, baritone voice and eye patch helping him earn the nickname, “The Baron of Country Music.”

Dan Fulkerson, a young DJ and aspiring songwriter in early 1960s Bangor, Maine, hitchhiked the roads around the city in hopes of catching a ride northward to Aroostook County. Truckers often gave Fulkerson a lift, and they traveled Route 2A northward from Haynesville, a tiny town equal in size to Dick Curless’ birthplace. Route 2A was long considered one of Maine’s most unforgiving roads (“highway” would be giving it far too much credit), but at the time, it was the only way to Aroostook County from points south. The winding, secluded route could be impassable in the winter months, and it supposedly claimed its share of truckers’ lives.

Fulkerson had intended to pitch his song to Johnny Cash but instead chose Curless, preferring a local artist who could identify with Route 2A. His choice turned out to be a good one, as “Tombstone Every Mile” topped out at No. 5 on the Billboard country music charts.

The focus of “Tombstone Every Mile” is the road Fulkerson traveled as a tag-along in big rigs, one he described as “a stretch of road up north in Maine that’s never ever, ever seen a smile.” Specifically, Fulkerson’s lyrics described only the portion of the road passing through the Haynesville Woods, just a few miles north of Haynesville.

The two-lane road was known for a few harrowing 90 degree turns virtually invisible to a driver not acquainted with the route. Its location experiences average high temperatures below the freezing mark three months of the year, low temperatures below freezing nine months annually, and snowfall an average of seven months. When Fulkerson wrote the lyrics of “Tombstone Every Mile” and referred to the road as a “ribbon of ice,” he was not exaggerating.

The most memorable phrase in Curless’s recording is, “if they buried all the truckers lost in them woods, there’d be a tombstone every mile.” Now, pinning down the number of truckers killed along Route 2A is difficult; in fact, the precise length of the stretch of Route 2A Curless sings of isn’t easy to determine. But local folklore supports the claim that the road isn’t exactly the most hospitable route for drivers of any vehicle.

Route 2A is frequently noted as “the most haunted place in Aroostook County,” if not in the entire state. Locals and ghost hunters tell of paranormal experiences along the road, but few tales mention trucks. Still, even if “a tombstone every mile” isn’t an accurate statistic, the road has apparently snuffed out more than its share of lives.

After riding “Tombstone Every Mile” into the top 5 singles charts, Curless recorded on and off over the years. When he did, he relied on his first song’s success and firmly implanted himself in the country sub-genre of trucking music. Other Curless hits through the mid-1970s included “Tater Raising Man,” “Travelin’ Man” and “Highway Man.” In addition to “The Baron,” Curless left no doubt he was a “man.” As many low to mid-level U.S. country artists do, he gained his greatest popularity overseas and ended his career in Branson, Missouri. He passed away in his beloved home state of Maine in 1995 at the age of just 63.

It’s hard to say how much of “Tombstone Every Mile” is fact versus fiction. Even in Haynesville, locals debate the question. One longtime resident told a group of college kids what he thought of the stories. “All I know is that the road is a dangerous one,” he said. When asked if he’d change his mind if he saw a ghost, he answered, “Sure. If [someone] sat down beside me and vanished, I’d believe in ghosts.”

Today, Route 2A is even more lonely and secluded than 50 years ago. Interstate 95 now stretches from Maine’s southernmost point to Houlton, about 25 miles northeast of Haynesville. Truckers bypass the dangerous and reportedly haunted Route 2A in favor of faster, safer interstate travel that ends at the Canadian border.

Still, the legacy of “Tombstone Every Mile” lives on. Notable accidents have and continue to occur along Route 2A. In fact, just two years after Curless became a mainstay of trucking music with his recording, two young girls were killed on Route 2A. Both girls died on August 22, 1967. And both were hit by tractor-trailers.

Until next time, keep the rhythm, and watch out for those blind twists in the road ahead.

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.

There was not one, but two 10 year-old girls killed on the road in Haynesville in August of 1967 when a tractor-trailer went over at the same time, by the same truck. I was only 7 years-old, but I was there when it happened. My family from Waterville were going camping when we came across a truck on its side with wheels spinning, (this is what I remember). The driver, who didn’t seem to be badly hurt, was climbing out of the cab. We were the first car on the scene, so had to wait for the police to answer questions. My older brother told me that Dad went to a store to call the police, (no cell phones then). I remember the driver waving the traffic on like he was irritated, probably just in shock and not wanting people to gawk. I also recall my father telling my mother that the girls looked like two dolls laying there. The thing that most haunts me about that incident was when the grandmother of one of the girls came and screamed her granddaughter’s name over and over, “Oh, Melody, oh Melody!” (The girl was Melody S—–). That voice still rings in my head today. We went home after that since we didn’t feel like camping anymore. Ironically, the girl Melody, (can’t remember the other girl’s name), used to live in the town where I now live, quite a way from Haynesville, and my aunt taught her at the local elementary school. I know Melody’s brother and we’ve talked about the accident. He was 12 when it happened.

I guess you didn’t research Fort Fairfield before writing this article, because a current population of 3500, is a good deal bigger than 120.

Population in 1932, was about 8-10,000. As for a “secluded” northeastern town, University of Maine has 2 campuses, one 15 miles away and another 1 hour further north.