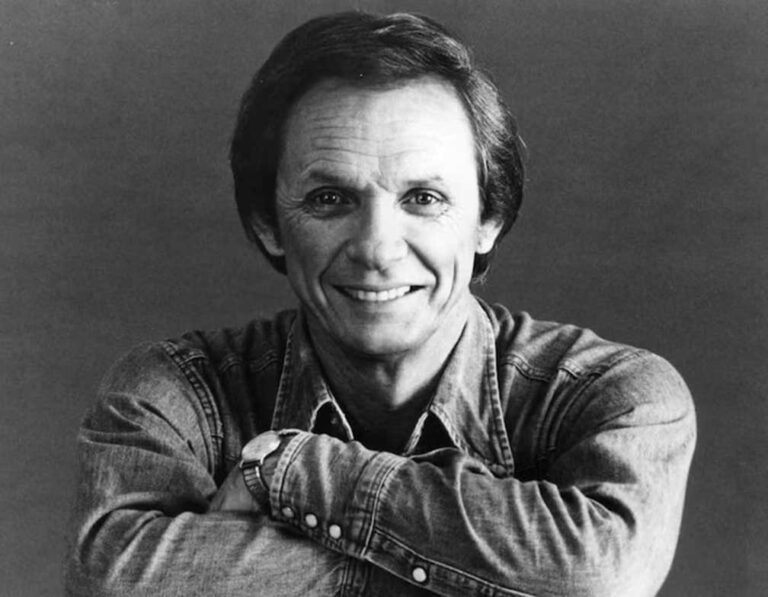

Mel Tillis started stuttering following a bout with malaria at 3 years of age … but he didn’t realize it until he entered first grade.

He always told it like this:

I came home the first day and I said, “Mama, do I stutter?”

And she said, “Yes, you do, son.”

And, I said, “Mama, they laughed at me.”

And she said, “Well, if they’re going laugh at you, give them something to laugh about.

And that was my first day, I think, in show business.

It was also in first grade that Tillis learned something special about his speech. Even though he couldn’t talk like most kids, he could sing with the best of them. In fact, he could sing better than the best of them. His teacher had him sing in front of the class to build his confidence, and soon she paraded him around the school to sing in all the classrooms.

In short order, the Tampa, Florida, native was a budding star. He soon learned to play the drums and guitar, and when he was 16, he won a local talent show.

During a stint in the U.S. Air Force, Tillis formed The Westerners, a band that played local clubs on Okinawa. Following his years in the Air Force, he returned to Florida and worked odd jobs. He eventually was employed by a railroad company — and one of the perks of the job was a free railroad pass. He took his and hopped a train to Nashville, where he auditioned for the Acuff-Rose Music company.

The verdict? Rose advised Tillis to return to Florida and work on his songwriting. Well, Tillis did just that, and eventually his path led back to Nashville, where he began writing songs full-time.

In 1957, Web Pierce recorded one of Tillis’ songs, “I’m Tired,” taking it to No. 3 on the charts. Soon the likes of Ray Price and Kitty Wells were making hits out of Tillis’ songs, and his prowess as a songwriter led to his own recording contract with Columbia Records. Before the 1950s closed, he had two hits of his own, “The Violet and the Rose” and “Sawmill.

Still, his greatest success came as a songwriter.

Tillis owed a lot of his success to Webb Pierce. The songs “I Ain’t Never” and “Crazy Wild Desire” became hits for Pierce. Tillis also wrote “Detroit City,” a hit for several artists including Bobby Bare. Then, in the late 1960s, Tillis’ “All the Time” became a No. 1 hit for Jack Greene. The songwriting continued as other artists recorded Tillis-written tunes like “The Snakes Crawl at Night,” “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” and “Mental Revenge.”

Finally, in 1968, Tillis had his breakthrough as a singer in his own right, hitting the Top 10 with “Who’s Julie?” He followed his initial success a year later with “These Lonely Hands of Mine” and “She’ll Be Hanging Around Somewhere.” And in 1970, he reached No. 3 with “Heart Over Mind.” Songs like “Heaven Everyday,” “Commercial Affection” and “Arms of a Fool” followed.

In 1972, he reached the top of the charts with his own version of “I Ain’t Never.”

Tillis continued to enjoy success with his recordings throughout the early 1970s, but he reached the pinnacle of his success with MCA records in 1976. “Good Woman Blues” and “Heart Healer” both reached No. 1, and Tillis was awarded the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year award. The Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame also inducted Tillis the same year.

In 1979, He recorded “Coca-Cola Cowboy,” a song that connected him with motion pictures when it was selected to be on the soundtrack for Clint Eastwood’s “Every Which Way but Loose.” Other hits during this time included “Send Me Down to Tucson,” the racy “I Got the Hoss,” and “Lying Time Again.”

Tillis continued to have hits into the early 1980s, when his movie career went into full swing.

He’d had previous experience with motion pictures with roles in 1967’s “Cottonpickin’ Chickenpeckers” and 1975’s “W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings.” But it wasn’t until the 1980s that he drew demand as an actor. Tillis played roles in “Smokey and the Bandit II,” “The Cannonball Run” and its sequel “Beer for My Horses,” “The Villian” and “Uphill All the Way.”

As his career waned, Tillis opened a theater in Branson, Missouri, where he and a dozen singers who were also on the downslide, kept their careers alive. Fans flocked to the tiny city to see them perform their old hits. It wasn’t until 2007 that Tillis was inducted into the Grand Ole Opry, considered by many to be country music’s most coveted honor. The same year, he received his induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Tillis was always a master at including comedy in his act — something his mother first alluded to after his bad experience on his first day of school. Often self-deprecating, Tillis was still ashamed of his stutter in the mid-70s, until the one and only Minnie Pearl reminded him that the audience was not laughing at him. Rather, they were laughing with him. She also told him to never step on an audience’s laughs. “They are too hard to get,” she said.

Beginning in 2016, Mel Tillis suffered from a series of illnesses, and he died Nov. 19, 2017, in Ocala, Florida.

Until next time, remember what Mel Tillis always realized: A disability is what you make of it. In Tillis’ case, it became a gimmick that made him a star.

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.