Rules are rules, but for every rule there are exceptions, and that’s when things can get murky.

That’s certainly been the case ever since the ELD mandate went in to effect. Dec. 18, 2017, was just another day for those who’d been using ELDs for years. But for other drivers and carriers who want to operate within the regulations but hadn’t necessarily always been worried about the fine details, it was the start of an age of anxiety, knowing that every little move and non-move was on the record.

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration recently tried to provide clarity to two areas of most concern and confusion: personal conveyance and the agricultural exemption, by providing their official definitions and some regulatory counsel for each.

But there are so many “what if” questions around both categories, not to mention many drivers with questions not only how to follow the regulations but to show they’ve been followed on the official log.

In order to clear the air a little more on these issues, ELD manufacturer EROADS conducted a webinar July 24, cohosted by Joe DeLorenzo, FMCSA’s director of enforcement and compliance, and Soona Lee, EROAD’s director of regulatory compliance, explaining how and when these rules apply and how to record them.

DeLorenzo opened by acknowledging that determining when driving can be considered personal conveyance can seem tricky.

The way to simplify it is to ask yourself two questions, he said: First, is the driver released from duty and second, is the driving for personal purposes only? There are several hard and firm rules within FMCSA guidelines about what definitely is and isn’t allowed, DeLorenzo said. But if you keep those two guidelines in mind, it starts to get clearer whether the personal conveyance rule applies or not.

“I think it’s important to talk about personal conveyance for what it really is,” DeLorenzo said. “It’s an off-duty status. That’s where the whole consideration of whether something is personal conveyance starts.”

The original personal conveyance guidance was written in 1998. Since then, a lot of people have come up with creative and convenient interpretations of the rules that may be well-intentioned but not strictly accurate.

Take commuting, DeLorenzo said, “This one can get people a little tripped up.”

Commuting between home and a terminal or work sites using a CMV is considered personal conveyance, he said. “Where this one gets trickier is where the driver is under dispatch when they leave the house,” DeLorenzo said.

If a driver loads up before going home anticipating he’ll hit the road first thing in the morning, or if the driver gets up and heads straight to a pick-up, that changes things because the driver is then “under the direction of a carrier.”

Another common question is when a driver stops at a rest stop for the night then wants to go get something to eat. That drive to the restaurant is personal conveyance. But if along the way you stop somewhere to fill up the gas tank, that would be considered work-related, so the trip would no longer qualify as personal conveyance.

“It’s the intent of the driving that matters,” DeLorenzo said. It doesn’t matter whether you’re laden, or even if you’re bobtailing. Are you off duty and is the movement strictly for personal reasons?

DeLorenzo illustrated his point using another common scenario. Suppose it takes longer than planned to load up and you’re running out of hours to find a safe, legal place to park. That extra time beyond your 14 hours that it will take find a place for the night would fall under personal conveyance. The same would be true if you stop somewhere and a law enforcement officer tells you that you have to move on.

“There’s no reason why your 10 hours should get broken up over that,” DeLorenzo said. “This is where you put an annotation in, you put a note in that says what happened and why.”

It doesn’t matter if looking for a place to stop happens to bring you a little closer to your destination, DeLorenzo said. But if you stretch that search out, skipping past rest stops in order to get a little further down the road, then it’s a problem.

The key to personal conveyance is documentation, Lee said. ELDs include a “personal conveyance” duty-status option. The thing to remember is whenever that status is engaged off-duty personal conveyance time will be noted and an explanation for the mileage must be entered into the log.

Another option, Lee said, is to remain logged out during the personal conveyance and, again, have that written explanation to account for the miles driven.

Keep in mind, she added, that carriers can establish their own limits about personal conveyance that are tighter than the actual regulation, so drivers need to know what their carrier’s rules are.

DeLorenzo joined Lee in stressing that personal conveyance time is off-duty time, but drivers must stick to the same safety standards they always drive by. And while there are no regulations about how much time a driver can spend on personal conveyance, it is important to use enough of those 10 hours of down time to get adequate rest.

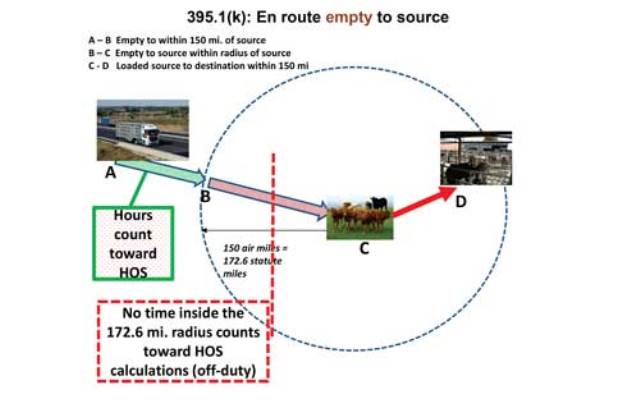

The agricultural exemption makes the time a driver spends within a 150-air-mile radius of the source of an agricultural commodity exempt from counting toward Hours of Service.

Much of the uncertainty about this exemption has to do with definitions, DeLorenzo said. “A lot of people get confused over the term ‘agricultural commodity.”’

An agricultural commodity is any “nonprocessed food, feed, fiber or livestock,” DeLorenzo said. “Nonprocessed,” he added, means it can be packaged, but it has to still be in its original form.

“As long as it’s still a head of lettuce, it’s fine. If it’s in a bag of mixed greens, well, it’s not an agricultural commodity anymore.”

Another word that hangs up a lot of people is “source,” DeLorenzo said. The source can be an original source, like a farm or ranch, or an intermediate facility, such as a grain elevator or sale barn.

How the exemption works, DeLorenzo explained, is to put a circle with a radius of 150 miles around the source. “If you’re operating within 150 air miles of the source, then the Hours of Service regulations do not apply.”

The clock stops the moment you enter the circle on your way to the source. Loading up, traveling to other stops to load or unload, then heading off to the drop-off location, none of that goes toward HOS.

The clock starts as soon as you leave the circle. If that destination is 300 miles away, you could cover half of that before the clock starts toward HOS, DeLorenzo explained.

DeLorenzo clarified a few points. If loading occurs at more than one site, the ag exemption radius for the entire job is based on the location of the first loading point. You can’t create a string of exempt zones.

If you drive out of the circle and the clock starts, then your route brings you back into the circle, then the clock stops again, DeLorenzo said. A trip could spend three hours inside the circle. Then you could drive outside the circle five hours, spend three at the destination, drive five hours on the return, reach the radius, then drive two hours more to get home.

That trip took 18 hours, but the first three hours and last two hours were within the 150-mile radius. Outside the radius, there were 10 hours driving, 13 hours total counting toward HOS, so it’s all good.

Obviously, it’s important to log the ag exemption properly, Lee said, and there are three options.

The first is to simply not log in until you reach the 150-mile radius. All the driving that had been done would show as “unidentified driving.” You then reject those unidentified miles and annotate that time was ag exempt, then begin normal recording.

Option two is to log in at the beginning then annotate the exempt and nonexempt time later, Lee said. “You could also use the personal conveyance option to separate that time you’re ag exempt. That’s kind of a tidy little option, just because it puts everything in the off-duty line.”

Lee and DeLorenzo noted that the key thing they wanted to get across is that a driver’s log doesn’t begin and end with the ELD.

“Everybody thinks there’s this magic thing that says, ‘hi, you’re in violation’ and spits out a ticket,” DeLorenzo said. “But what the law enforcement officer gets is your full ELD record including the annotations.

“The ELD device is not ultimately making the decision whether you’re compliant or not. That’s the law enforcement officer’s job, and they’re going to review those annotations.”

To watch the webinar in its entirety, click here.

Klint Lowry has been a journalist for over 20 years. Prior to that, he did all kinds work, including several that involved driving, though he never graduated to big rigs. He worked at newspapers in the Detroit, Tampa and Little Rock, Ark., areas before coming to The Trucker in 2017. Having experienced such constant change at home and at work, he felt a certain kinship to professional truck drivers. Because trucking is more than a career, it’s a way of life, Klint has always liked to focus on every aspect of the quality of truckers’ lives.

Thank you for this information. I have forwarded it to some friends and they say thank you also. Everything was clear and simple to understand.

great job made the water quite clear removed the mud I just hope the DOT reads this it is definitely a topic that comes up especially now that harvest is coming up

Thank You

Thomas A Goodman

Triple B Trucking US DOT #2510996