When you think about America’s progress, it’s easy to look at the advanced number of roads and highway systems as a symbol of that progress. They’re the paths to our own personal progress: traveling to work or school every day, to the next delivery or adventure. We rely on roads to advance ourselves and to continue improving the nation for the sake of progress.

But the path to collective progress means improving the nation’s roads. The U.S. needs new access routes, climbing lanes, repavements, and more. In the American Society of Civil Engineers’ most recent “Infrastructure Report Card” released in early March, the group gave America’s infrastructure a mediocre overall score of C-. Although this grade is progress from the D+ given in 2017, the need for more roads, accessibility, and infrastructure investments is evident.

That means the nation needs trust — trust in its own Highway Trust Fund (HTF). It’s what feeds the new roads, bridges, and highways we’ve depended on for decades. The HTF is powered by the federal fuel tax, which is set at 18.4 cents per gallon for gasoline, and 24.4 cents per gallon for diesel fuel.

But the federal fuel tax hasn’t been increased in more than two decades. Meanwhile, inflation has steadily risen to 79% since 1993, the same year the federal fuel tax was last increased.

Since 2008, the HTF has primarily been funded through a series of general fund transfers from the U.S. Congress, rather than efforts to increase the gas tax. Funds provided by Congress have reached $158 billion, including $83.6 billion from the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, according to the Congressional Research Service.

“Increases in fuel consumption kept revenues growing until the recession that began in 2007,” according to a March 1 report from the Congressional Research Service. “Since that time, improving fuel efficiency and slower growth in vehicle mileage have led revenue to level off in most years, and spending from the HTF has consistently outrun highway user revenues.”

The FAST Act — originally signed by President Barack Obama in 2015 — was reauthorized by former President Donald Trump in October 2020. This provided an additional $13.6 billion for the HTF. But that authorization has an expiration date of September 30, 2021.

Policymakers have avoided increasing the fuel tax “since such actions will noticeably increase the cost of fuel for nearly all constituents in the short-term,” according to the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI).

At this rate, the HTF will be drained by 2022, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

“Increases in fuel consumption kept revenues growing until the recession that began in 2007,” according to the Congressional Research Service’s report. “Since that time, improving fuel efficiency and slower growth in vehicle mileage have led revenue to level off in most years, and spending from the HTF has consistently outrun highway user revenues.”

What will we rely on when there’s no funding left to fix our roads?

For the Truckload Carriers Association’s (TCA) Vice President of Government Affairs David Heller, the focus for funding relies on the fuel tax.

“There is an opportunity to make the Highway Trust Fund sustainable again, and doing so in a manner that is the most cost-effective is going to be the fuel tax,” he said.

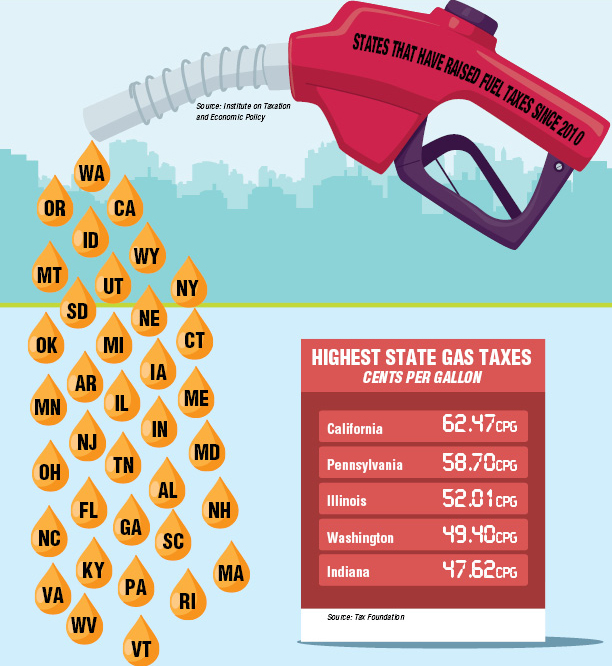

Although it has not been increased since 1993, at least 36 states have already increased their own fuel taxes.

“While the standing belief is that it can’t get done, the reality is that it actually is getting done,” added Heller. “It has been done in 36 states, over the past 10 years, which have raised their fuel tax to help support roads and bridges.”

Mandated tolling and a vehicle miles traveled (VMT) tax have also been thrown out as sustainable options for rebuilding the HTF, although Heller disagrees with these measures.

The need for a VMT tax — a potential widespread tax or per-mile charge on all vehicles — could eliminate electric vehicle (EV) parity issues. Today, EVs do not contribute to the fuel tax since they do not visit the pump, which is where the tax is collected

“While the trials, tests, and equipment are out there, the VMT hasn’t made inroads answering the questions that really need to be taken into consideration right now,” he explained. “VMT is not ready for a primetime funding mechanism. We’re just not there yet.”

Initial implementation of a VMT could total billions of dollars, according to Heller.

“Quite frankly, there’s no need to incur those costs right now when we’ve got other mechanisms in place, i.e. the fuel tax, to actually get us there,” he said.

Administrative costs of tolling, along with wear and tear on roads and bridges, and avoidance of tolls cause concern for Heller.

“People may try to circumvent tolls and send cars and trucks on roads and bridges that aren’t used to having that kind of traffic, thus making roads and bridges deteriorate quicker because they’re just not built for that type of traffic as people try to evade the toll booths,” he said.

That does not mean increasing the fuel tax comes without consequences.

“Make no mistake, there are some shortcomings to increasing the fuel tax,” added Heller.

In addition to EVs escaping taxation, more fuel-efficient vehicles are continuously being developed that will visit the pump less, therefore creating disproportion in taxation.

“EVs are not paying nearly as much, to say nothing to the fact that today’s fuel tax rates are woefully short of what they should be, so they’re not capturing the dollars on what they should, but raising it (the fuel tax) hopefully helps make up the difference,” noted Heller.

There’s also a chance that those with a lower income may not be able to afford the increased fuel tax. That is a similar consequence of the VMT, as well.

According to ATRI’s “A Practical Analysis of a National VMT System,” the annual financial transaction costs could be as high as $4.3 billion and would require charging VMT users almost 40% more to cover collection costs.

“The fuel tax right now represents the single greatest economically sound manner of highway funding. It has the lowest administrative costs attributed to it, meaning that it represents about 1% of overhead costs,” Heller said.

To provide adequate funding with an increase, the fuel tax would need to be increased to five cents a year for the next four years for a total of 20 cents, or five years, at 25 cents.

“That’s just a yearly increase of a nickel per gallon to eventually be capped at 25 cents, then indexed to the cost of inflation using the CPI, or Consumer Price Index,” added Heller. “That would make it adjustable on an annual basis.”

With that increase, the HTF has a chance of being sustainably funded and trusted once again.

Hannah Butler is a lover of interesting people, places, photos and the written word. Butler is a former community newspaper reporter and editor for Arkansas Tech University’s student newspaper. Butler is currently finishing up her undergraduate print journalism degree and hopes to pursue higher education. Her work has been featured in at least nine different publications.